Because Billy Payne had studied up on everyone from the king of Bhutan to Arkansas' favorite son, he knew what to say to Bill Clinton, and how to say it. So Payne suggested they play golf sometime. When Clinton said yes, the smiling Payne added a promise. He told the president of the United States and the leader of the free world, "I'm gonna whup your ass."

There came a heartbeat's silence from Clinton.

Then, a roar of laughter.

"You had two strong leaders, two sons of the South in Billy Payne and Bill Clinton," says Mack McLarty, a boyhood friend who became Clinton's most trusted political adviser. "The president had met 'Billy Payne'—the strong, entrepreneurial, Southern charmer—a hundred times before he met Billy Payne. What Billy said, he said in just the right manner.

"The president loved it."

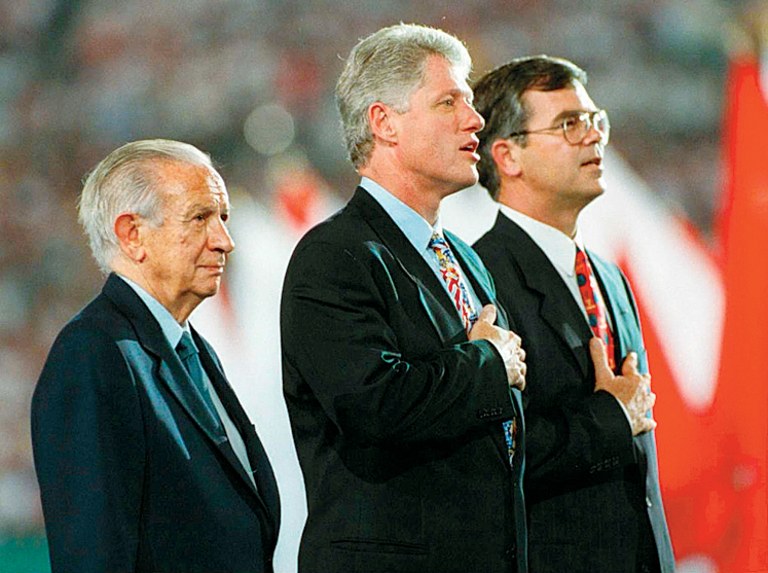

Payne had been just another Atlanta lawyer shuffling real-estate papers. Clinton had been the boy governor of a state that didn't matter. But at the moment of their meeting, in the run-up to the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, they were high-flying players on the world stage. Payne not only conceived the idea of the Games in his hometown, he made it happen, just as Clinton transformed implausibility into reality by winning the presidency.

McLarty had it right. William Jefferson Clinton of Arkansas knew William Porter Payne of Georgia. Because he became president by working with his own beguiling audacity, Bill also knew this about Billy: When a son of the South smiles and says he's gonna whup your ass, he intends to whup your ass.

Billy Payne is a master at it. At 6-feet-2 and 230 pounds, playing alongside future NFL stars at the University of Georgia, he was an all-conference defensive end. Now 59 years old, he has survived two triple-bypass heart operations and a family history of heart disease; both his father, the Georgia football legend Porter Payne, and Porter's father died early of heart attacks. Not only did Billy persuade International Olympic Committee members to give the Games to a city some couldn't find on a globe, he also wheedled $40 million sponsorships from corporate chieftains who once refused his phone calls.

Not to mention winning a bride. On first meeting Martha Beard at a fraternity party, Payne told her, repeatedly, "I'm really a nice guy when I'm sober." To prove it, he showed up the next morning in her dorm lobby. Three years later, June 29, 1968, they were married. Thirty-eight years and counting.

The victories surprise no one who has been in Payne's force field. "Billy was extremely competitive," says Vince Dooley, his coach at Georgia in the late 1960s. "The most competitive individual I've ever known," says Dick Yarbrough, a key man on Payne's staff during the Olympics. An Atlanta businessman long familiar with Payne sees a resolute man practiced in the nuances of the competitive art: "The quintessential, modern-day good ol' boy. A chameleon. Intimidating, yet polite. Loud, yet courteous. Smart, though aw-shucks."

The latest measure of Payne's grit, guile and doggedness is his comeback from a decade-long drift after the Games. As nice as a seven-figure rainmaker job and board memberships are—Payne is now a partner in Gleacher Partners, a New York-based investment firm with offices in Atlanta-—they do not satisfy a man who lusts for the arena's heat. "He was making money, but I think Billy felt useless," says Melissa Turner, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution reporter on the Payne beat for years. Exacerbating the emptiness was a consensus that the Olympics, stigmatized by a fatal bombing and trashed by a cheesy downtown flea-market bazaar, had failed to put Atlanta among the great international cities. Then a federal investigation of a Salt Lake City bid for the Winter Olympics spilled over onto Payne's team with charges of vote-buying.

"In the early '90s, people talked about Billy as the next governor," says Marty Appel, who directed the Olympics public-relations staff for 18 months. "Then he had to almost go into hiding after the Games. It was a shame, because he is a man with great charisma who I think is a genuine hero for Atlanta history books."

Now Payne steps again into the arena. In May 2006, nine years after becoming a member, Payne was named the sixth chairman of Augusta National Golf Club. This April he presides over the club's Masters Tournament for the first time. An extraordinary exception to the rule of Augusta chairmen unfamiliar to the public, Payne comes to the job as a celebrity. But rather than make clear how he'll perform as chairman, his public profile is so rich in detail it can support what would seem to be contradictory conclusions. He could deliver Augusta National directly from the 19th century to the 21st. He also could be the man Augusta's members have proved they want, Clifford Roberts re-born.

FacebookPinterest

FacebookPinterestFOLLOWING THE MODEL

Clifford Roberts was the New York investment banker who, with Bobby Jones, built Augusta National in 1931 and became the club's original chairman. He was infamous for a management style that ranged from dictatorial to tyrannical. Roberts also made the occasional stop at pettiness. Because Augusta's members created a scoring system based on pars and birdies, Roberts always partnered with an assistant pro. He counted on that nervous young man for birdies. "One day," a veteran of those moments told me long ago, "Mr. Roberts' partner had made no birdies. So, at the turn, Mr. Roberts said, 'Bobby, you go on in the shop and send out a pro.' And he did."

Roberts' stern practices were so effective that even 30 years after his death they seem to be models for his successors, among them Hootie Johnson. A courtly South Carolina banker long identified as an advocate of civil rights, Johnson yet rose up in anger in 2003 when Martha Burk, representing the National Council of Women's Organizations, demanded that the club accept women as members. Johnson declared that if Augusta changed its policies, it would do so of its own accord and not "at the point of a bayonet." The resulting applause from Augusta faithful caused the old plantation grounds to fairly quiver.

Payne has bowed to the sainted Jones and to Roberts. In a conference call with reporters last spring, he said, "I am humbled by the thought of following in the footsteps of the great men who have preceded me, and I am well aware of the customs and traditions which they held so dearly and advanced so steadfastly." He hoped "to reflect proudly on those traditions, and to demonstrate time and time again my love and affection for Augusta National Golf Club, and the Masters."

That Billy Payne—polite, courteous, aw-shucks—is not the Billy Payne known to the Atlanta politician Bill Byrne, who says he remembers a hot-necked conversation with Payne during the 1996 Olympics. In the politician's memory, it goes something like this:

Byrne, piqued: "You can stick it in your ass."

Payne, beyond caring: "Who are you again?"

Details of the meeting are secondary. Payne now says, "I don't remember Mr. Byrne." Dick Yarbrough, the Payne aide who most often dealt with Byrne, calls the story a lie. What's likely true is the attitude. When Billy Payne has an idea in mind, his hair might explode into fire and he wouldn't notice.

"My daddy told me, 'Never was a horse that couldn't be rode or a rider that couldn't be throwed,' " he says. So a politician with his knickers in a twist may tell Payne to perform anatomically painful feats, but Porter Payne's son will look down from the great height of his idea, bemused by a little man without a clue. Students of the Roberts/Payne management style might be reminded of an old Persian saying: The dogs bark, the caravan passes on.

Augusta National is neither America's only private men's club nor its most anachronistic. There is San Francisco's Bohemian Club. The Bohos are mostly old, rich, white geezers of political and corporate influence. The club, formed in 1872, is widely known for its annual male-bonding, networking-galore camp-out for a couple thousand members and guests in a giant redwood grove. (The 125 camps have names such as Toyland, Dog House, Hill Billies. "They're like Cub Scouts with their dens," a member's wife told The San Francisco Chronicle.) During a bacchanalian fortnight, the Bohos stage elaborate pageants (men in drag do the female roles) and perform a mock human sacrifice under a 40-foot-tall owl.

"I went to the Grove once, determined not to be impressed by anyone," says a man with journalism in his background. "Why would I be impressed? I'd met everybody, interviewed everybody. Then I saw a guy urinating on a redwood. I looked again. My God, it was Wally Schirra, the astronaut. I was impressed."

Perhaps Augusta National simply does a better job than the Bohemian in preserving its secrets. But if manly men frolicked in frocks for Bobby Jones and Cliff Roberts, or if geezers whizzed on the azaleas, historians have not yet discovered those events. Nor is there the equivalent of harsh judgment handed down by a sitting president. Richard M. Nixon's words were preserved by his Oval Office tape-recording system in 1971. He called the Bohemian Grove gathering "the most faggy goddamned thing you could ever imagine, with that San Francisco crowd.

I can't shake hands with anybody from San Francisco."

Enter Martha Burk. She declared that Augusta National, albeit a lawful private club, is host to an internationally televised event sponsored by publicly owned corporations that would not, and could not legally, practice sexual discrimination; therefore, it is Augusta's moral duty to admit female members. That argument failed. Now Burk has moved beyond Augusta National to confront corporations whose chief executive officers are members of men-only clubs.

"As for Billy Payne," Burk wrote in an e-mail to me, "many sportswriters claimed he was 'his own man' when he took over the chairmanship. I couldn't disagree more. It is clear that he is Hootie's man, and would never have gotten the nod if he had not promised to continue barring women. … Billy Payne has the opportunity to change that black mark and erase the legacy that Hootie has created, but I don't think he has either the courage or the conviction to do it."

It might be instructive here to pause and behold with certain awe the airy structure supporting Burk's opinions. She cannot know the process by which Payne became chairman; unlike the Bohos, the Augustans can keep a secret. The most Payne would say during last spring's teleconference is that Johnson inquired "would I be interested in the undertaking if and when he chose to retire"; "other members" were included in talks, and no conditions were placed on the job. When I asked him to elaborate, Payne declined.

There is also this about Burk: What she doesn't know about Payne is mostly everything. She has never met, spoken with, worked with, or, as a matter of logistics, stood near enough to him to imagine where she would insert a bayonet's point. She might be surprised to learn that people who know Payne believe Augusta will admit women during his tenure.

FacebookPinterest

FacebookPinterestPayne joins Johnson at a pre-tournament press conference before the 2006 Masters.

The Atlanta businessman familiar with Payne says, "He will bring the club, let's say, 'to' the 21st century—in a politically correct way, behind closed doors, bullying if need be." "Women will enter," says broadcaster Bob Costas, "when it can be seen as a victory and not a capitulation." A Payne critic during the Olympics, political activist and Baptist church pastor Rev. Tim McDonald, says, "I feel that Billy feels in his heart of hearts that it's time to open up that door, and he's going to do it tactfully, quietly, and as a positive thing." After years at Payne's side directing the chief's public relations, Dick Yarbrough believes "an absence of pressure" will be significant: "If the special-interest groups really want women in, they will give Billy some time and some room." Mack McLarty calls Payne "a contemporary person who will be thoughtful and do the right thing." "Billy is not a status-quo guy," says his church pastor, Dr. Chris Price, "and I can see him making changes that would make Augusta a better, richer experience."

Because Linda Stephenson is a golfer and was one of several women high on Payne's Olympic staff for years, the natural question is: Might she be Augusta's first woman member?

"No, no," she said, "you're not going to get me into that."

Atlanta's singular Olympic success came in women's events. It sold more tickets for those events alone than Barcelona sold for all its events four years earlier. "Maybe Billy has learned that life as we know it will not end if a woman darkens the door at Augusta," says Dick Pound, a Canadian sports official with extensive Olympic experience. "If so, maybe Augusta National can move cautiously into the 19th century."

The 19th?

"Yes."

In answer to Burk and on the women's issue, Payne delivers a hard line in clipped tones: "Our club will deliberate privately over all issues regarding membership, and other than that we're just not going to talk about it."

The caravan passes on, moving at Billy Payne speed.

THE SON AND THE FATHER

What makes Billy Payne run?

"His father," says A.D. Frazier, Payne's No. 2 during the Olympics.

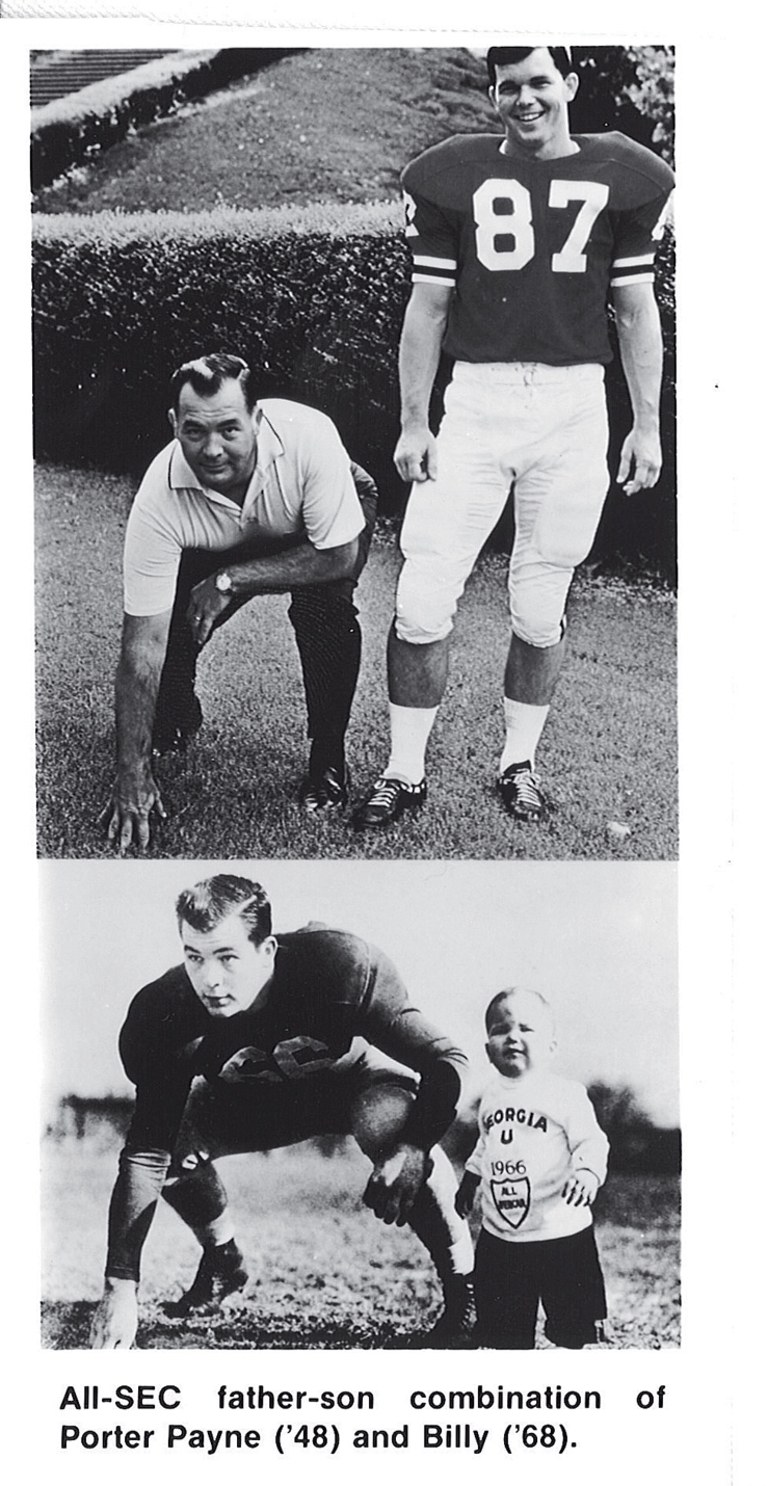

When Porter Otis Payne died in 1982, Billy Payne saw thousands of mourners at the funeral. "My father had more friends who loved him dearly than anybody I have ever known or heard about in my life," he told a reporter.

A photograph made in 1949 shows 1-year-old Billy standing alongside his father, the Georgia lineman, handsome and powerful, down in a three-point stance, a shadowy colossus looming over the tow-headed tyke in a shirt with lettering that reads "1966 All-American" at "Georgia U." Someone must have thought the juxtaposition was cute. But the child seems confused, about to cry. It's an image that might cause a boy to wonder if he ever could be as big as Daddy.

FacebookPinterest

FacebookPinterestBilly as a star at Georgia with his dad (top); as a tyke with his dad in Georgia gear.

"My dad was the personification of the big teddy bear, just a giant of a man, much bigger than me," Billy says now. "He played at Georgia at around 230, which was very big for the day. Afterward, he got heavy, up to 270, 280. But he didn't really look it because he had a massive bone structure. I could barely reach around his wrist with both hands."

Porter Payne "was the original Boy Scout, always positive, untouched by the slightest whisper of ever having done anything wrong," says Edwin Pope, the Miami sports columnist, a Georgia student in Porter's time. "I drove him back to Atlanta from an Auburn game once, and I remember him being the nicest guy I'd ever met."

John Donaldson was Porter Payne's teammate and later coached Billy at Georgia. He remembers the father as "bigger than Billy but not as fast, an outstanding, fundamentally sound football player who played both ways, a 60-minute man. One of the best Georgia ever had."

Donaldson saw the father in the son. They'd both been high school stars, Porter a fullback, Billy a quarterback/linebacker. At Georgia they became linemen. "As difficult as it is to go from the limelight to the line—that was proof of their unselfish attitudes," the old coach says. "How they most were alike was, they were honorable men. You could trust Porter to tell you the truth, and Billy's the same way."

Porter Payne grew up without his father, once a sheriff in North Carolina, who died of a heart attack at age 38. Porter was a 16-year-old high school senior in Atlanta when he married Mary Lenda Lowe. A year and a half later, in 1946, the Paynes were parents of a daughter; a year after that came Billy. After graduation from Georgia, rather than play professional football, which in 1950 paid laborer's wages, Porter said no to the New York Giants and went to work for an insurance company in Atlanta.

"An exceedingly mature, sweet person," Billy Payne says of his father. Then, a caveat: "Up to a point, the sweetest, kindest person you have ever seen. It took a lot to get him mad, but once he reached the boiling point, nobody wanted to be around him."

Three men in a car learned that. Billy remembers it. He was a boy, 10 or 11 years old. He rode in the back seat as his father and mother left Atlanta's Piedmont Hospital driving north on Peachtree Street. Mary Lenda had suffered a miscarriage, Porter was taking her home. "Three guys in the lane next to us yelled out disrespectful things to my mom, a beautiful, beautiful lady," Payne says. "Remember, my mom and dad were still in their 20s. And my dad didn't take it very well."

Porter Payne ran the miscreants off the road, putting his car against the driver's door, and "in less than a minute, two of them were lying on the ground, all bloodied up. The driver had rolled his window down and was desperately trying to climb out the other side. So my dad went over there and made short work of that last one."

Payne told the story and then worried that it left a distorted picture of his father. "The point I'm making," he says, "is that my dad was the sweetest man in the world until you challenged his integrity or his family. And then, wow, he was right back to his athleticism. Boy, he could do it. He was a lot of man."

A son could respect, admire and wonder if he ever could be that man. Years later, when Billy Payne made a commencement-day speech in his alma mater's football stadium, he used the first two minutes to explain that his father always asked him one question, the same question, a question that shaped his life.

Every time Billy played at Georgia's Sanford Stadium, Porter came to sit in Row 50. Still, he never saw Billy make a play. He hid his face in his hands until he heard a whistle signal a play's end. Billy told the assembled graduates, "I was always mystified by my dad's nervousness, because his assessment of how I played in each and every game was the single most important criterion by which I judged my performance. I loved him so much and so respected his opinion that I would always ask him after every game, 'Dad, how do you think I played today?'

"You know, my dad would invariably answer that question with another question when he would ask, 'Billy, tell me, do you think you did your very best?'

"And you know the sad part? Never once in my athletic career, after all of those many performances on this field, was I able to answer my dad's question by saying, 'Yes, Dad, I did my best.' "

As Payne's business and civic achievements came, so did the question. "He would always respond, 'I'm proud of you, Billy, but have you done your best?' My dad died in 1982 at the age of 53, never once hearing his son say, 'Yes, Dad, I did my best.' "I carry that burden to this day. … "

Fathers and sons can be mysteries to each other, inspirations forever, momentarily burdens. Edwin Pope, the columnist who knew Porter Payne as a student, felt a suggestion of that ambivalence just before the Atlanta Olympics when he mentioned Porter to Billy. "It was like Billy didn't want to hear it, because he'd heard it all his life," Pope says.

‘In the early '90s, people talked about Billy as the next governor. Then he had to almost go into hiding after the Games’ – Marty Appel

Whatever the drivers of Billy Payne's search for achievement—genetic gifts, unflagging resolve, ego, a need for his father's approval—they moved him from football to achievements he had never imagined.

On Feb. 8, 1987, after chairing a building committee that raised $2.2 million for a new sanctuary, Payne went to the St. Luke's Presbyterian senior pastor, Moss Robertson. He knew that Atlanta had rejected bidding for the Olympics a decade earlier. "I want to get the Olympics here this time," Payne told the pastor.

Robertson now says, "I thought but didn't say, Only you, Billy. Thank God for Billy."

In time, the son had a different answer for the question the father always asked: "The tireless pursuit in the Olympic effort, from start to finish, if I've ever done my best—at anything other than my family—that's it. And my dad knows about it. I just wish I could have shared it with him in his time here."

After the Olympics, Payne joked that he might need to rest 10 years before trying the next big thing. Now, on schedule, comes Augusta.

FacebookPinterest

FacebookPinterestPayne brought the Olympic flame to Atlanta literally and figuratively, then joined Clinton and Juan Antonio Samaranch for opening ceremonies (below).

FacebookPinterest

FacebookPinterestAUGUSTA AND THE GAMES

Payne is uncertain when he first visited Augusta National, either in 1966 or 1967 (on a fraternity brother's ticket). He first played there in 1990 with the Bobby Jones contemporary Charlie Yates. ("I shot in the 90s, maybe 100.")

Because Payne believes Augusta National's golf course is "the most beautiful piece of real estate in the world," he wanted it central to the Atlanta Olympics. He worked with members to arrange tee times for IOC voters and once wrote to then-chairman Jack Stephens that the golf course, as a destination point for travelers from around the world, "is our Mediterranean Sea."

‘If you are going to entrust the Holy Grail of golf to anyone, I cannot think of any King Arthur better than Billy Payne’ – A.D. Frazier

Payne wanted golf restored to the Games for the first time in nearly a century. Augusta National had agreed to be the host for men and women from around the world, the LPGA Tour alongside the PGA Tour, Fiji alongside Finland. "It would have opened up Augusta National to both women and minorities," Dick Yarbrough says.

But the initiative was abandoned when the Atlanta City Council, famous for such ruckuses, provoked a racial and sexual controversy over Augusta's reputation as an exclusionary club. A.D. Frazier says, "Losing Augusta broke Billy's heart." But the loss was not disappointing, Payne says, because of any social issues: "For me, it was never a political or social issue. The Council made it one for them. I was just doing what I thought was best for sports in the state of Georgia."

Now, as chairman of Augusta National, "Billy must feel he has died and gone to heaven, because he truly has a deep love for golf," Dick Pound says. Frazier goes mythological on the idea of Payne and Augusta: "If you are going to entrust the Holy Grail of golf to anyone, I cannot think of any King Arthur better than Billy Payne."

He is already running at Payne speed. His wife, Martha, says, "He's at Augusta three days a week usually: long meetings, a lot of listening—and golf." Here is Payne on contemporary Masters issues.

• Yes, a Masters-only ball is an option held in reserve for a dread day—not nearly here yet, he emphasizes—when equipment renders Augusta National defenseless.

"I embrace totally what we have long advocated, which is, we're going to take whatever steps are required to ensure and preserve the integrity and competitiveness of our golf course. We became increasingly concerned a number of years ago as the distances the ball traveled were going up rather substantially. We thought that an alternative might be some agreement on the specifications of the ball that would limit the distances and therefore protect the course. Generally, we made folks aware of that as an option. We still preserve it as such. But let me say first, we were very pleased with the way our course withstood the competitive pressures last year. Second, there does seem to be a slowing of the rate of increase in distances. That slowing makes us hopeful that we'll never have to utilize the ball as an option."

• Yes, he wants PGA Tour winners automatically eligible.

"We're looking at that with a positive inclination because I think many of us have missed the excitement of a guy winning a tournament and saying, 'I'm in the Masters,' not, 'Thank you for a million dollars.' That's a special moment. What's held us back has been monitoring the new tour season as they are now defining it. As those specifications become known, we'll be ready fairly soon to announce our intentions."

• In the name of all that's holy, yes, yes, he dearly wants Arnold Palmer, in Arnold's own time, in Arnold's own way, to serve as the Masters ceremonial starter in the tradition of Sarazen, Snead and Nelson.

"I'm excited about the prospects of Arnold doing us that honor as soon as he wants to do it. Every time I'm privileged to see him, I'm going to remind him that we'd love to have him. I have no doubt whatsoever that his presence would be uniformly, positively embraced by all of our patrons and fans all around the world. It would just be magnificent."

Hand Payne this: He is a quick study for a man who frittered away most of his first 40 years on something other than golf.

"I was not a big golfer," he says, "and I was not a good golfer. I played socially, with business partners, maybe once every six weeks. I wasn't very good at it, and I didn't like doing things I wasn't good at."

His attitude changed in the years preceding the Olympics. He played at dawn on Sundays, accompanied by only his security man. He doesn't hit balls. ("I like to keep score, so I'm not a good practicer.") He soon became good at golf in the way that star athletes are always good at making hard things look easy. ("I fell in love with the game.") Before long, his Index was 3. Last fall at Augusta, on a 6.8, from the member tees, he shot a 73.

A Reliable Source describes the chairman's swing.

"Ooooooh, my."

Say again?

"He wraps the driver around his ear, way past parallel, and hits it 300-plus."

John Daly-esque?

"It's past 'past parallel'—it's vertical," says Identity Withheld to Protect an Old Friendship. "And that's with the lob wedge. Amazing, but he's scratch with his short game. It's the long irons that give him trouble."

As to the winner of the Beguiling & Charming Sons of the South match, Payne is diplomatic. Rather than rush to an accounting, the chairman first talks about other stuff involving the president of the United States. Such as snipers.

"Some high-level Secret Service official, maybe the director, was walking with us," Payne says of that day on a course near Washington. "I kept noticing these guys dressed in ninja suits always staying way ahead of us. We'd finish a hole, and they'd walk ahead. And I was dying to ask, 'Who are those guys?'

"He said, 'That's a special detail of armed-forces snipers. They're on a protection detail.' I said, 'Man, they're so far away.' And I remember, specifically, he said, 'Three seconds' notice from about 100 yards away, they can shoot your eye out.' "

The Secret Service man told Payne the snipers were rotated into the jobs based on competitions. Only the best make the presidential protection detail.

"I remember being real careful about patting the president on the back," the chairman says.

So, who whupped?

"I probably beat him on gross score," Payne says. "I do not remember who won the bet."

THE DANCE WITH DEATH

For the longest time, Payne said the question about his death was not what would kill him but when. Now the man with the scary history of heart disease says, "People talk too much about my health. I think I have it under control, and I know I've been very fortunate. I am an obsessive physical-fitness nut, and I'm in the best shape of my life. I have no plans of checking out of here early."

At 59, Payne is tall and lean. Down 30 pounds from his football weight, he still carries in his shoulders, chest and erect bearing the suggestion of an athlete's strength. His workout routine: "Five minutes of ab stuff first. Then 10 minutes of stretch bands. Thirty minutes of weight training. Biceps/chest one day, triceps, legs, lats the next day, and I'll do those as aerobic things, no rest between reps. Now we're 45 minutes into it, and I'll finish with 45 minutes on either the StairMaster or the elliptical."

How often for all this?

"Every day."

Every day?

"I'm having too much fun with life now," he says. "I don't want to be interrupted." He held out his family's Christmas card, a photograph of him and Martha with their eight grandchildren. "Look here," he says. "That's enough reason right there."

Besides, there is Augusta. There is golf. There also are fish.

FacebookPinterest

FacebookPinterestPresidents, pooh-bahs and panjandrums of all stripes have come and gone in Payne's life. But for 31 years, Payne and seven buddies have gathered twice a year for fishing trips. Because boys will be boys, the anglers have named their group the Fishermen's Academy for Relief and Thought.

"If you spell that out," Peter Candler says, "you'll see that now we're a bunch of old ones." Then, backpedaling at a great rate of speed, Candler asked a reporter, please, don't use that unless you run it by Billy first.

So the matter was presented to William Porter Payne.

There came a heartbeat's silence from Payne.

Then another moment, and …

A roar of laughter.

The Masters: The Shot I'll Never Forget